Introduction

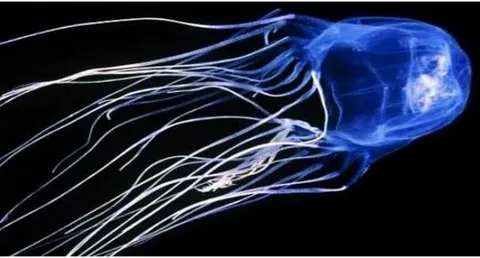

It sounds like something from a sci-fi horror movie: a predator the size of a sugar cube, transparent, nearly invisible in the water—and capable of killing a healthy adult in mere minutes. No fangs, no claws, no dramatic attacks. Just a gentle brush, and the countdown begins.

Meet the Irukandji jellyfishUnseen Killers of the Jungle: How These Camouflaged Predators Ambush Without a Sound, one of the ocean’s most dangerous—and mysterious—inhabitants. Native to the warm coastal waters of Australia and recently sighted as far afield as Florida, this minuscule jellyfish has puzzled scientists for decades. Despite being only about the size of a fingernail, the Irukandji’s sting unleashes a devastating syndrome that includes extreme pain, nausea, skyrocketing blood pressure, and—if untreated—death.

But here’s the truly chilling part: scientists still don’t fully understand how it works.

In this post, we’ll explore the strange biology of the Irukandji jellyfish, the effects of its sting on the human body, and why its behavior continues to baffle marine biologists in both Australia and the United States. We’ll also touch on how its growing presence in warming waters signals deeper ecological changes—and how to stay safe in its increasingly large territory.

Oceanic Nightmare: An Overview of the Irukandji Jellyfish

The Irukandji jellyfish isn’t just one species—it refers to a group of small, box jellyfish found primarily in the waters of northern Australia. The most notorious member of this group is Carukia barnesi, first identified in 1964 by Dr. Jack Barnes, who famously stung himself (and his son!) to prove the jellyfish’s link to a set of mysterious symptoms affecting swimmers.

How big is it, really?

- Bell size: 1 to 2 cm (smaller than a paperclip)

- Tentacles: Up to 1 meter long, nearly invisible in water

- Habitat: Coastal waters, reefs, and sometimes far from shore

The Irukandji might be small, but the medical consequences of its sting—collectively known as Irukandji syndrome—are massive.

What Makes the Irukandji Sting So Dangerous?

Unlike larger box jellyfish like Chironex fleckeri (the “sea wasp”), Irukandji jellyfish don’t deliver an immediate, obvious sting. Most people don’t even realize they’ve been stung—until 20 to 40 minutes later, when all hell breaks loose.

Symptoms of Irukandji Syndrome

- Severe, shooting muscle pain (especially in the back and kidneys)

- Vomiting and relentless nausea

- Elevated heart rate and dangerously high blood pressure

- Profuse sweating and agitation

- Psychological symptoms: sense of impending doom, panic, hallucinations

In extreme cases, it can lead to cerebral hemorrhage, cardiac arrest, or stroke. And because the jellyfish is so small and transparent, medical responders often struggle to confirm a sting in time.

Why Scientists Still Don’t Fully Understand the Irukandji

Despite decades of research, the Irukandji jellyfish remains enigmatic. Its venom affects the nervous system, cardiovascular system, and even mental state—but scientists are still piecing together how it operates on a molecular level.

Here’s why it’s still largely a mystery:

- Low availability: It’s incredibly difficult to capture and study in labs.

- Fast deterioration: Irukandji die quickly in captivity, making research challenging.

- Tiny size: The small venom yield complicates chemical analysis.

- Unusual venom composition: Unlike other jellyfish, Irukandji venom seems to cause a delayed, systemic reaction rather than localized pain.

According to research published by James Cook University in Queensland, researchers still haven’t fully mapped out the proteins in Irukandji venom that cause its uniquely severe symptoms.

A Warming Ocean, A Growing Threat

Irukandji jellyfish used to be a primarily tropical concern. But with climate change pushing sea temperatures higher, these jellyfish are expanding their range.

Documented Sightings Beyond Australia:

- Florida, USA: In 2017, stings linked to Irukandji-like jellyfish were reported along beaches in the Florida Keys.

- Western Australia: Regions that never had recorded incidents are now reporting hospitalizations.

- Japan and Thailand: New hotspots emerging in warming waters.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), warming sea surface temperatures have enabled tropical marine species like Irukandji to migrate northward along the U.S. coastlines.

Source: NOAA Climate Trends

How Irukandji Jellyfish Affect Tourism and Healthcare Systems

Australia’s tropical coasts—especially Queensland—depend heavily on tourism. But during “stinger season” (November to May), beaches post “Jellyfish Warning” signs, and tourists are advised to wear full-body stinger suits or avoid the water entirely.

Economic impact in Australia:

- Estimated losses: Millions in potential tourism revenue

- Lifeguard training: Major investment in venom response protocols

- Medical costs: Emergency response for severe stings costs thousands per case

Growing awareness in the U.S.:

- Emergency protocols in Florida hospitals now include potential Irukandji sting procedures.

- Public education campaigns on jellyfish stings have been rolled out by NOAA and local governments.

Staying Safe in the Water: What You Can Do

While Irukandji jellyfish stings are rare, they’re increasing in frequency. Here are a few practical steps for swimmers, divers, and beachgoers:

Tips for Australia and U.S. Beachgoers:

- Swim in designated areas with lifeguards and safety nets.

- Wear protective clothing (stinger suits or wetsuits).

- Check local advisories before entering tropical or subtropical waters.

- Avoid swimming at dusk or dawn, when jellyfish may be more active.

- Don’t rely on visibility—Irukandji jellyfish are nearly invisible.

If you believe you’ve been stung and experience symptoms after swimming:

- Call emergency services immediately.

- Do NOT apply freshwater—only vinegar should be used to deactivate remaining stingers.

- Keep still and calm to slow venom absorption.

Table: Comparison of Venomous Marine Encounters (Australia vs. USA)

| Species | Country | Danger Level | Common Season | Known Fatalities | Average Response Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irukandji Jellyfish | Australia / USA (Florida) | Very High | Nov – May | 2–3 (Australia) | 15–30 minutes |

| Portuguese Man o’ War | USA (East Coast) | Moderate | Year-round | Rare | Immediate pain |

| Box Jellyfish (Chironex) | Northern Australia | Extremely High | Nov – Apr | 70+ (since 1884) | Instant reaction needed |

| Sea Nettle | USA (Chesapeake Bay) | Low | Summer | None | Mild reaction |

Key Insights from the Irukandji Phenomenon

The Irukandji jellyfish is more than just a medical oddity—it’s a symbol of how complex, delicate, and dangerous ocean ecosystems can be. From healthcare systems to climate change impacts, this tiny creature forces us to rethink how we approach marine safety and environmental science.

Key takeaways:

- Size doesn’t equate to threat: Some of nature’s deadliest creatures are microscopic.

- Marine medicine is evolving: But still lags behind when it comes to venom analysis.

- Warming oceans mean shifting threats: Tropical species are showing up in temperate zones.

- Public education saves lives: Early symptoms recognition is key to preventing fatalities.

Real-World Examples in Action

Australia: The Cairns Hospital Case

In 2023, a 34-year-old man was stung while snorkeling near Cairns. Within 25 minutes, he was vomiting uncontrollably and experiencing full-body muscle spasms. Quick administration of painkillers, intravenous fluids, and anti-hypertensives saved his life.

According to the Queensland Government Health Department, the region sees an average of 40–60 Irukandji stings annually, mostly near popular beaches.

Source: Queensland Health

USA: Florida Keys Incident

In 2021, several swimmers near Key West reported sudden severe pain, nausea, and hallucinations after contact with an unidentified jellyfish. Though not officially confirmed as Irukandji stings, symptoms were consistent with the syndrome. The incident prompted increased NOAA monitoring and emergency medical training for Florida’s coastal regions.

Conclusion: The Deadliest Things Are Often the Least Obvious

The Irukandji jellyfish is proof that we still know remarkably little about the oceans that cover more than 70% of our planet. In a world fixated on large predators like sharks or crocodiles, this nearly invisible floating phantom reminds us that true danger often hides in the smallest, quietest places.

Understanding creatures like the Irukandji isn’t just about surviving a trip to the beach—it’s about preparing for a future where ocean life continues to shift and evolve in response to climate change, globalization, and human activity.

Call to Action

For beachgoers: Learn the signs of Irukandji syndrome and respect local beach warnings—especially in Australia and Florida.

For environmental leaders: Invest in marine biology research and support data sharing between Australia and U.S. institutions.

For everyone: Stay curious. Stay aware. Because nature doesn’t always announce itself.